The warriors of Japan, the Samurai, lived in a warrior society where martial etiquette ruled all aspects of the warrior’s life. A comparison to the ancient martial laws would be the modern U.S. military’s Uniform Code of Military Justice. This is a set of laws quite outside of the civilian laws.

If you have served in the military you may remember such etiquettes as how and when to salute, or how to address a superior officer in conversation. These rules govern a soldier’s actions concerning the observation and acknowledgement of superior rank as well as reinforce a certain social standing within the military. This has a direct correlation with the bow in Japanese martial arts. Many other rules governed the lives of the ancient Japanese warrior, as they do the modern military soldier. It is a society within a society.

Part of the martial training of the warrior remains constant throughout history. A soldier will train with his primary and secondary personal weapon, train in military tactics, navigation, modes of transportation, and forms of unarmed combat. This hasn’t changed over the centuries. Modern soldiers do the same thing. Perhaps the forms of weaponry and transportation have changed, and technology helps the modern soldier, but the training methods are relatively the same.

Another aspect of warrior society that remains constant is the percentage of soldiers to civilians. Soldier always made up a small part of society, and soldiers are usually heavily armed while civilians are lightly armed or not armed at all in a peaceful society, but make up the larger segment. Soldiers can face a constant combat environment during war or times of civil unrest, while civilians rarely face violent confrontation during their lifetimes. When they do however, civilians are at a significant disadvantage as they usually do not have a weapon or training that will allow them to defend themselves. Most often a civilian will have to resort to unarmed forms of self defense in order to protect themselves against an attack by another.

From the necessity of the unarmed to defend themselves came the adoption and adaptation of military unarmed defensive methods by the civilian population. Early on, soldiers who were not at war or who were unemployed began to teach civilians methods of unarmed self defense for money. As wars dwindled, and civilians became more interested in self defense, martial arts schools developed, much to the disappointment of many soldiers of the day.

A unique aspect of the martial way that was brought by the Japanese warriors to their civilian students was spiritual development. Spiritual development in conjunction with traditional martial arts is an accepted partnership today, but there was little understanding of its role in the warrior ways. Even the civilian students of the samurai did not understand.

Originally the spiritual aspects were a separate discipline from the ways of war. A soldier became, through harsh training, a dealer of death. His job was to learn to fight in battle when called upon to do so by his lord. He was also required to perform security details and collect taxes and debts for his superiors. All of these duties provided ample opportunity for violent confrontations. A soldier had to be highly trained.

In contrast to the harsh physical and mental warrior training, soldiers would find mental and physical solace in practicing spiritually oriented cultural arts quite apart from their warrior training. I must note again – apart from their warrior training.

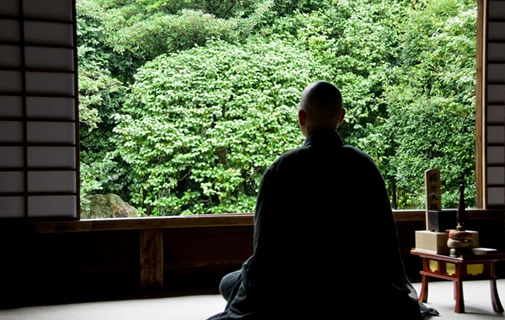

The search for inner peace and tranquility led battle hardened samurai to arts such as Zen meditation, Tea Ceremony, wood carving, painting, calligraphy, gardening and other typically Japanese cultural and religious art forms. Whereas one side of the warrior was fierce and deadly, the other was quiet, placid and polite. Whereas a warrior could be harsh and brash if he had to, he could also be cultured and educated.

Training in these seemingly diverse disciplines did not occur together however. One did not learn meditation and the use of the spear from the same teacher. One did not learn how to throw an opponent and break his bones from the same person who taught him how to find tranquility in the austerity of the Tea Ceremony. These disciplines were separate, as were the instructors for very good reason. The harmonious spiritual arts were an escape and a tool to generate mental calmness for a warrior whos martial life was anything but harmonious or spiritual.

So how have these diverse disciplines become intertwined? Through misunderstanding. For the warrior, it was important that he be able to keep a calm and focused mind during the heat of battle so that he could think clearly and fearlessly in chaos. Many of the spiritual disciplines he practiced apart from his warrior training helped him achieve this calmness under stress.

When civilians began to train, there was little understanding of the entire warrior lifestyle. To the civilian, they were being taught the “secrets” of the Samurai, when in fact they were being taught a mere fraction of the Japanese warrior’s knowledge. There was little need to understand how to use the sword in battle as civilians were not allowed to carry swords. It is the same today, as civilians are not allowed by law to carry M-16 automatic rifles. What the civilians did learn was how to use unarmed techniques in order to stop other unarmed or lightly armed civilians from hurting or killing them. Such is the same today. Modern martial art students are not going to learn how to disarm an American soldier in full battle dress. It simply isn’t needed.

When westerners were first introduced to Japanese martial arts at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, not only were they fascinated with unarmed self defense training, and how easily it defeated western boxing and wrestling, but also with Japanese society as a whole. When Japanese traditions were brought back to the United States, they were mixed together, unlike they existed in Japan. The “Martial Arts” was more of a “cultural art” than a fighting art as it appeared in America. A student would learn some unarmed self defense, something about swords, something about Tea Ceremony, something about Zen, etc – all put into one “mixing bowl”. Thus was the beginning of the misunderstanding – a misunderstanding that still exists in the martial art community in the West today.

To the Westerner, martial art techniques meant you would be the winner in a fight. To the Westerner, the Samurai used meditation and learned Zen and made gardens in order to help them in battle – therefore martial art technique combined with the spiritual arts made you a better fighter. Wrong. Because these disparate disciplines existed in the same society, and sometimes within the same person does not mean they go together or are to be learned together. They are quite opposite, and their value exists in the fact that they are opposite and must be learned and practiced apart from the other for their full value to be realized.

The modern warrior, the military soldier does not need to meditate or garden, or observe rock formations, or grow small Japanese trees in order to be effective in battle. His technical and tactical knowledge (along with some luck) will make him successful or unsuccessful in battle. However, if a warrior finds himself with an unruly and chaotic mind because of the constant rigors of battle and unending harsh training, he may find benefit in what spiritual endeavors bring to the mind and body. Then again he may not. There are many soldiers who thrive on adrenaline and chaos, and find themselves at a disadvantage in the spiritual, social or educational realm. It is a very individual thing. But a common thread exists here – modern combat training does not include spiritual musings, and few spiritual endeavors include fighting and killing. They are exclusive of each other, and thus retain their value and power over the individual.

YET – the misunderstanding still exists and is repeated generation after generation in the civilian martial arts in the West. Why? Because there is still a fascination with the cultural aspects of the country of origin of the martial arts civilians practice. They are enamored with the clothing, the language, the decorations, the spirituality, the ceremony and the etiquette. These things are of little value when combined with fighting methods. They only hold value outside of the training and discipline of the warrior methods.

So what can be done to increase both the value of warrior training and spiritual training? Simply learn and practice them separately from each other. Set aside time to train your body and mind in the martial ways, and set aside other time for calming of the mind and spirit through other proven means. Then you can feel the power of both individually. Mixing them together does nothing but muddy the waters. The mind finds it difficult to allow itself to be brutal enough to defend ones self, at the same time as it tries to find peace and harmony. At that point, both disciplines become less of what they are meant for and mostly neutralize each other.

The methods of self defense are brutal and dangerous. Training can be physically harsh in order to harden the mind and body against the realities of a physical attack. You must allow your mind to embrace the moment and respond violently to an attack, unencumbered by any moral or spiritual restraint. This is the only way one can survive a brutal attack by someone of superior size and strength, or with a small weapon such as a knife, club or gun. Do not allow this training to dominate your life however. See it for what it is. You have made the decision that you might need to defend yourself against an aggressive encounter, and you train in order to be able to fend off any attack against you or your loved ones. That is a smart and noble pursuit. But do not let it make you become a “weekend warrior” or an imaginary soldier in your mind. You are not – you are a civilian using martial arts (arts of war) in order to increase your chances of success in a fight.

In contrast to the violence in society and the violence of martial art training (if you are training correctly), find solace in meditative or spiritually contemplative arts if you find that helps you deal with life in a calmer and more controlled manner. If you have a violent personality and are full of rage, these methods of harmony may help you remain more stable. If you are over emotional, some of these arts may help you separate yourself from uncontrolled emotions. If you find yourself in constant altercations because you are a Corrections Officer, Police officer, Bodyguard or a Bouncer, you may find spiritual training an asset to offset the chaos and violence of your job. But this is an individual pursuit. It is not for everyone, and is not necessary for everyone.

The point I would like to drive home is that training in the martial arts, those arts designed to escape from, strike, throw, choke, break, injure, maim, and possibly kill an attacker should not be learned in the same place from the same person as the spiritual arts. Nor should they be practiced in the same place or at the same time. When this is done, you are perpetuating a cultural misunderstanding that has existed in the West for a century, and has done nothing but lessen the effectiveness of both disciplines.

Recent Comments